Local And Global Variables

Here’s a short program that prints "Hello class" to the JavaScript console.

function setup() {let person = "class";console.log("Hello", person);}

Here's a modification, that moves the greeting code (line 3, above) into a separate function. (This is similar to what we did for corners, on Tuesday.)

function setup() {let person = "class";greet();}function greet() {console.log("Hello", person);}

This doesn't work!

The setup function defines a variable named person. The greet function uses a variable named person. But it’s not defined!

Remember when I explained that defining a variable is like adding a word to a dictionary? Each function has its own dictionary. The setup function adds the word “person” to the dictionary for setup. The greet function has a different dictionary, that doesn't define this word (variable).

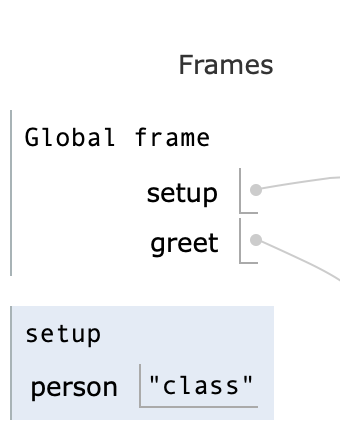

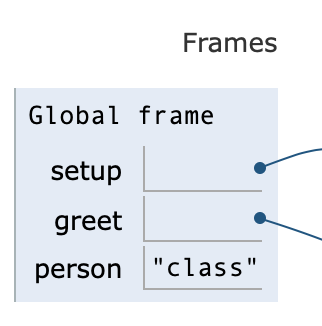

This link opens this program in JavaScript Tutor. Use the “Next >” button to step through it until you reach the error. The Frames column shows the “dictionary” for each function.

(JavaScript tutor calls these “frames”. I've been using the “dictionary” metaphor. You will also see them called “environments”.)

We can fix this by moving the definition of person outside of any function.

let person = "class";function setup() {greet();}function greet() {console.log("Hello", person);}

Try running this modified code. In the JavaScript Tutor window that you opened above, click “Edit this code”. (You can also get a new JavaScript Tutor window here.) Copy the code above and paste it into JavaScript Tutor. Leave the final line setup(); (or put it back after you paste) — p5.js call setup automatically, but JavaScript Tutor doesn't. Now click “Visualize Execution”, and step through the code with “Next >”. Note that this time, the definition for person is in the “Global frame”, that all code in the sketch has access to.

When person is defined inside a function, it’s a local variable, that can only be used in that function. When person is defined outside of any function, it’s a global variable, and all the code in the sketch has access to it.

In this latest sketch, person is both defined (let person) and initialized (person = "class") in one statement, on line 1. The definition tells JavaScript “this is a variable, that has a value”. The initialization tells JavaScript “this is what the value is”.

We can also split the definition and the initialization into two lines:

let person;person = "class";function setup() {greeting();}function greet() {console.log("Hello", greetee);}

This is useful in order to initialize the variable's value in one function, and use it in another.

let person;function setup() {person = "class";greet();}function greet() {console.log("Hello", greetee);}

You will see this pattern, of defining a global variable outside of any function and then initializing it in setup, all the time.

In this particular case, we could also pass the value of the person variable from setup to greet, as an argument. This is what we did with the corners function on Tuesday. Using that technique here would look like this:

function setup() {let person = "class";greet(person);}function greet(person) {console.log("Hello", greetee);}

Passing a value as an argument works here because setup calls greet. Try it in JavaScript Tutor!

This method wouldn't work if we wanted to get information from setup to draw, because setup doesn't call draw (p5.js calls them both). In this case, the global variable approach is necessary.

let person;function setup() {person = "class";greet(person);}function draw() {console.log("Hello", greetee);}